Like many people from the “south” my understanding of the Arctic is virtual in nature; most of my knowledge comes from information fed through my own culture and the media, including articles, books, films, and exhibitions. My project focuses primarily on Greenland, but one of my most profound impressions of the Arctic came from watching contemporary throat singer Tanya Tagaq improvise to the silent film Nanook of the North. This performance at the Museum of Fine Art in Boston, U.S.A. was a perfect reminder that works of art often say more about the cultures producing them than about the subject matter of the art form itself. It is important to pause and consider how our narratives about the Arctic are created, and to ask who is creating them today.

Nanook of the North is an American film directed and produced in 1922 by Robert J. Flaherty. It takes place in Northern Quebec, Canada and is acknowledged for its authenticity, but also for its oversimplification of the Inuit people. For example, the eating of raw meat is prominently featured and is considered by some to be emphasized to the point of creating a caricature of the Inuit, thereby reducing a complex culture into one that is seemingly primitive and simplistic. Tagaq is of Inuit heritage; she draws from throat singing traditions, but blends the traditional with contemporary genres such as punk and hip hop. She was both ambivalent and passionate when introducing the film; she did not critique it so much as she reclaimed her heritage by layering the experience of being a contemporary Inuk over the film’s representation of her ancestors.

Last summer I attended the first annual Arctic Futures Institute hosted by the University of Maine System Law School, the Climate Change Institute of U Maine and the World Ocean Observatory. One of the guest speakers was lawyer, Jessica Lefevre, who had several decades of experience working with clients in Alaska. She contrasted the Cartesian mechanical view of the world with the instinctual and intuitive views of her clients. She told the story of a village leader from Quinhagak who, like Nanook, was a master hunter. The leader spoke of his relationship with the whale being hunted; both he and the whale were responsible for sustaining the village. She urged policy makers to shift out of the Cartesian view when working with indigenous communities, to drop assumptions and listen to the truths of people who live in and have intimate knowledge of the Arctic. In this way, new customs and ways of relating to one another will emerge. This is the message I took from Tanya Tagaq’s performance as well.To better understand the region’s relationship to the world, it is helpful to cast backward in time.

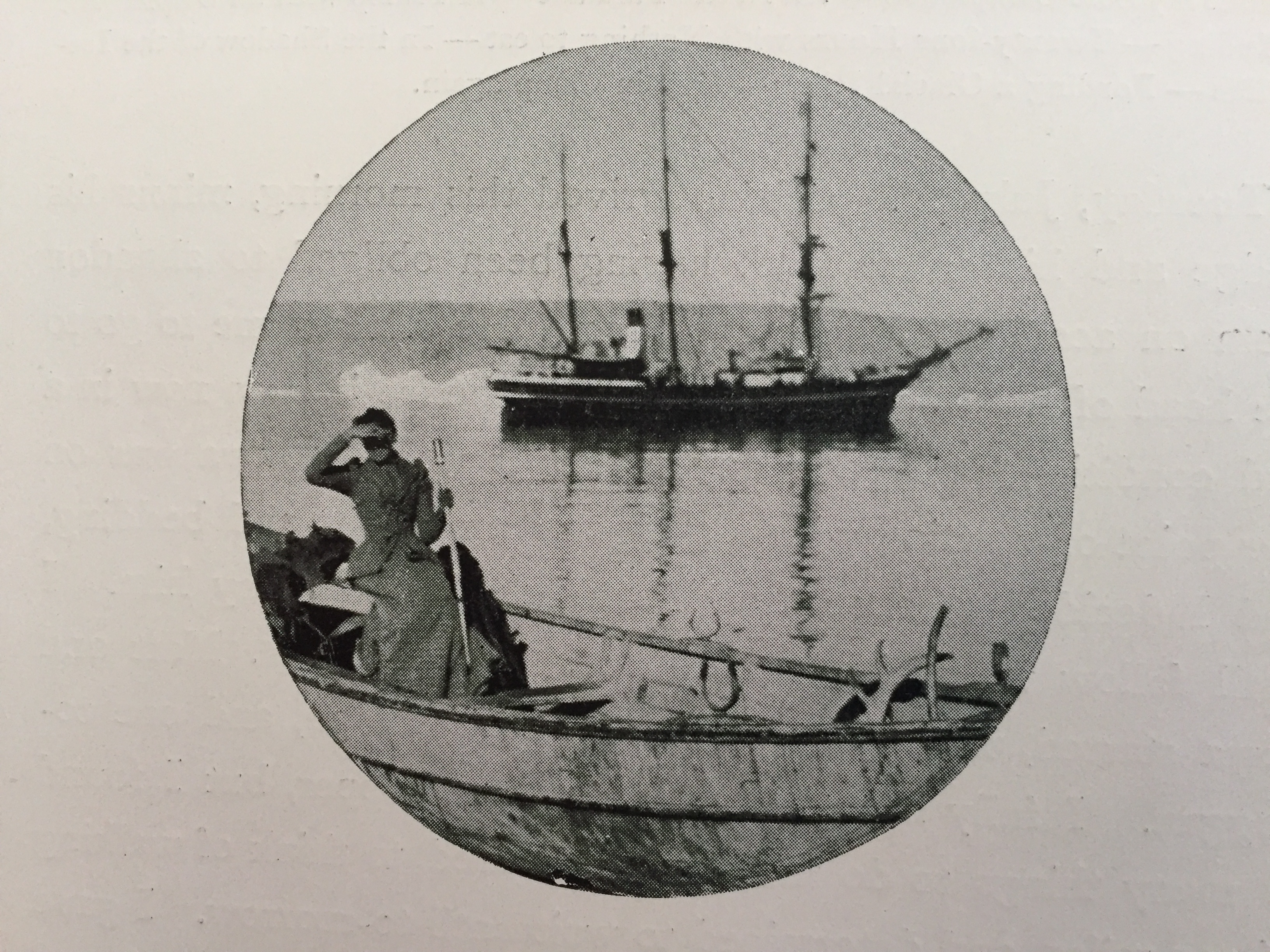

The Peary’s 1891/92 expedition aboard the steamship “Kite” provides a snapshot regarding the ethos of 19th century exploration. Arctic exploration reflected national identity, and Josephine Peary’s relationship to this identity was paradoxical. She played the role of the conventional wife who supported her husband’s reputation as a national hero while simultaneously disrupting the status quo by accompanying him on several expeditions to the far north. Regardless of how the Peary’s were viewed then or now, Josephine Peary left a compelling narrative about their first voyage together in her memoir My Arctic Journal, one that inspired me to record my own Arctic experiences.

In July of 2017 I visited the town of Ilulissat, Greenland; Ilulissat translates as icebergs, which are the reason I chose to visit this place. I wanted to see the monumental icebergs from the Jakobshavn Glacier make their way through the Ilulissat Ice Fjord into Disko Bay. From there, some bergs make it into the Atlantic Ocean; it is said that the iceberg that sunk the Titanic was from Ilulisat. I also chose this place because Godhavn in Disko Bay was the first port of call on the Peary’s journey. I wanted to compare Josephine Peary’s descriptions of Disko Bay to what it is like now. I also am curious about what it will look like in 100 years from now.

I was not alone in making the journey to see the icebergs; Ilulissat has a burgeoning tourist industry. It seems there is an urgency on the part of people from all over the world to experience the ice spectacle while it still lasts. In the center of town, there is an intersection with tourist services offered through offices on all for corners. One can book a midnight excursion through Disko Bay, helicopter rides over glacial terrain or buy hiking maps for traversing the UNESCO walking trails overlooking the Fjord. I scheduled a guided Kayaking tour to a small whaling village just north of Ilulissat. As it turned out, the weather was too windy for kayaking, so my small group was invited to a village home where a luncheon was prepared for us. Our guide was an entrepreneur from Spain, who was a co-owner in the kayaking business. We all sat at the dining room table and told stories about what brought us to Greenland. I talked about my interest in the Peary’s.

The entrepreneur, who had another life as a film producer, said he knew of Josephine Peary. He had worked on a film by Spanish Director Isabel Coixet that featured the French actress Juliette Binoche as Josephine Peary. The film was produced in 2015, and met with less than favorable reviews despite the strong acting and impressive cinematography. Even more so than in Nanook of the North, there are distortions of Inuit culture, but despite its weaknesses, the film touches upon contemporary themes of environmentalism and feminism. It is timely to reconstruct the Peary story in the context of post-colonial, post-industrial and feminist thinking. This helps deepen our understanding of the past and provides clues about how to progress in the future.

The Qajaq Journey animation will reference the Peary expedition, but rather than reenacting, it will provide a new narrative about Arctic exploration. The relationship of Maine to the North Atlantic depends on cultivating a greater understanding of cultural histories and differences, geopolitical and economic trends. We must also take into account the implications of climate change.